Article published in ZNER 2/1998

Article published in ZNER 2/1998 EU Feed-in Directive and Feed-in Legislation for Electricity Generated with Renewable Energy Sources versus Introduction Ratios.

Legal, energy and environmental issues in market access for renewable energy sources

The ongoing debate on the constitutional tenability of Germany's feed-in legislation for electricity generated with renewable energy sources (RES) - i.e. the question of its legality "at bottom" - and the operational or market economy appropriateness of the tariffs it contains - i.e. the question of their legality "in amount" - has reached a new dimension with the now beginning discussions about implementing the EU Commission's White Paper on renewable energy sources (inter alia with the aim of increasing the share of renewables in the EU's energy supply to 12 % by the year 2010) and the recommendation it contains on an EU feed-in directive.

This demand was based on proposals submitted by the European Parliament and the Committee of the Regions, by environmental organizations and organizations for renewable energy sources, regarding the EU Commission's Green Paper that had preceded the White Paper. The basis of these proposals was the fact that a comparison between the various feed-in rules for electricity from renewables comes to the empirical conclusion that statutory feed-in rules with guaranteed and roughly predictable tariffs (REFITs) at a level that reflects private operators' costs - as practised in Germany and Denmark - show the highest penetration rates by far for renewable energy sources in the electricity sector. While advocates attribute this to the unbureaucratic priority arrangements set forth in the feed-in law, critics of this new law see the reasons in what are by comparison higher tariffs. However, the argument that these are cost-covering rates as regards the invested funds and calculated depreciation periods has not yet been refuted.

The EU Commission's White Paper has not only adopted the recommendation for an EU feed-in directive, but gone even further and given it concrete shape. In the process, explicit reference is made to the terms of Article 14(3) of the directive for the internal electricity market, which provide for an entrepreneurial and transparent separation of electricity generation, transmission and distribution, and are of vital importance for the creation of a competitive market in the EU's electricity sector. Reference is also made to the ban under Article 7(5) preventing grid operators from discriminating against other grid users in favour of their own subsidiaries or shareholders. One possible solution cited involved remunerating auto-/independent producers (REAPs) according to the criteria of the avoided purchase costs at the "city gate", i.e. of the distributing firm, plus an ecologically-based premium of at least 20 %. The White Paper's reasoning in this case runs: "The tariffs ought to be at least in line with the costs saved by the operator for power generation in a low voltage grid, plus a premium that reflects the social and ecological benefits of renewable energy sources, as it does the nature of the financing, tax relief, etc." *** Hence, this proposal also complies with the polluter-pays principle as set forth in Article 130(r) (2) of the EU Treaty.

The proposal contained in the White Paper differs from the German feed-in law to the extent that the tariffs are not derived from the average working price for the electricity customer, but from the average costs of the purchased electricity and explicit use of a surcharge made on environmental grounds. In this respect, the White Paper refers to the priority arrangements for electricity from renewables made possible by Article 8, para. 3 of the internal electricity market directive. In a decision dated 2 July 1998, the European Parliament called upon the Commission to submit a proposal by 31 December 1998 "based on a right to feed in power subject to minimum tariff defined by the state."*** Also, it called upon the Commission to submit a new proposal by 30 June 1999 for an energy-related tax model that "gives concrete form to the principle of internalizing external costs and exempts renewable energy sources." ***

Among the various models providing for the market introduction of electricity from renewables that concentrate most of all on the question of a general feed-in right on the basis of tariffs defined and guaranteed by statute (German/Danish model), statutory tendering margins (British model), or stipulated tradable and certified quotas for renewable energy sources, the European Parliament has tended to advocate the first option. All the same, this says little about the direction the EU Commission's proposal will in fact take. Nor is adequate information available in the "Report to the Council and the European Parliament on harmonization requirements"*** submitted by the EU Commission on 24 March 1998, although there are signs of a move toward a quota model.

The point of such a quota model is to require consumers to cover a certain percentage of their electricity requirements from renewables. Since this is not universally possible to an equal extent, the consumer is to be obliged to acquire Green Certificates for the quota share, in which the distributing firms can trade. The idea is to ensure flexible management of the quota system.

However, the remarks on the harmonization report are, in several respects, one-sided, contradictory and incomplete, so that they have so far failed to provide an adequate basis for discussing consistent and purposive rules - in view of the aim of doubling the share of renewable energy sources in the EU by the year 2010 - providing for an expansion of such energy sources in the electricity sector. This being so, it is necessary to identify the specific defects in this report.

The defects in the harmonization report

1. Non-observance of the premises in the directive for the internal electricity market

One especially striking fact is that the report ignores some of the stipulations in the directive for the internal electricity market that are essential for penetration by renewable energy sources. For example, the harmonization report speaks of only one provision involving priority to be given to electricity generated from renewables at transmission level, viz. Article 8, para. 3. In fact, the directive contains three other essential provisions that are applicable to renewable energy sources as well: priority at distributor level made possible by Article 11(3); the common economic obligations set forth in Article 3(2); and the possibility of granting priority to domestic energy sources up to a share of 15 %, as set forth in Article 8(4). All of these provisions are explicitly defined as national priority options in order to prevent renewables or domestic energy sources from failing because of market barriers or being ousted from the market.

One point of conflict in the harmonization report, however, is the fact that these qualified national priority options have obviously not been taken seriously by the Commission. This is indicated by the warning against "distortions to trade" that might emerge in the EU Internal Market if, for example, "country X supports the generators of electricity from renewable energy sources by providing considerable financial assistance, while country Y operates a system of Green Certificates. Were country Y to allow power generators from country X to issue and sell Green Certificates in country Y, these electricity generators would receive double support. By contrast, anyone generating electricity in country Y and selling it in country X would receive no assistance at all."*** Still, this is really only the simulation of a problem, and the directive for the internal electricity market itself contains options for avoiding this situation.

Having national priority arrangements means that these must be sensibly shaped so as to apply only to feeders-in in the country where the plants themselves are located and where the electricity is also marketed. Hence, distortions to trade in the case of electricity from renewables can be avoided by using the directive, so that this by itself is no reason for demanding a European feed-in directive.

The need for one arises for two other reasons: in the first place, owing to the stated goal of rapid expansion of renewable energy sources, which - if possible in all those EU countries that have so far mainly had restrictive rules for renewables - requires adequate minimum tariffs, i.e. reflecting actual costs for investors and actually stepping up the pace of introduction; secondly, with a view to avoiding too wide a gap between electricity costs in EU member states, which can emerge where some states have priority arrangements reflecting actual costs, a correspondingly high share of renewable energy sources and, as a result, higher average electricity costs, while others, dispensing with priority arrangements, have a relatively low average price, so that distortions to trade can emerge in the course of a rapid expansion of renewable energies.

2. An overextended support concept

Conceptually, the harmonization report distinguishes between "favourable feed-in"***, to which the directive for the internal electricity market is said to be confined, and "support", which is said to be not allowed by the directive. In fact, no such conceptual distinction can be read into the directive. It would appear to be an arbitrary construct obviously designed to allow any form of actual priority to be branded as a support and, hence, to be denounced per se as an element foreign to the market. At no point in its remarks does the harmonization report say what it means specifically by "favourable feed-in". By contrast, it classifies as "support" - without exception - all promotional models for renewable energies, even where no monetary assistance is concerned. For example, it identifies as support purchase guarantees at a guaranteed price even on the basis of avoided costs (!), as well as introduction quotas, tax relief for electricity from renewables, the promotion of research and development, and even the award of "Green Certificates", which oblige consumers to acquire a certain share of renewable energies.

As a consequence, the support concept is so overextended that, apart from a complete market-economy laissez-faire throughout the EU that eschews any energy tax, anything else would ultimately be classified as "support" that would, ultimately, run counter to the competition principle. Article 92, para. 1 of the EC Treaty defines aid or support as an economic advantage granted directly by the government. This being so, it is inexplicable why, for example, the feed-in of electricity from renewables on the basis of the avoided costs of other electricity purchases is defined as a support. In the relevant court rulings, headed by the cartel division of the German Supreme Court (BGH) it has been established, on market-economy grounds in particular, that avoided purchase costs are the price criterion that must be conceded to auto-/ independent producers as well.

It would appear that the authors of the harmonization report, including those from the EU Directorate-General for Competition, do not wish to see the idea underlying Article 14(3) of the directive for the internal electricity market being applied to renewable energies. They implicitly adopt the reading of the conventional power utilities, which recognize only their own avoided fuel costs as avoided costs - a planned economy category based on the unity of production, transmission and distribution. It is equally inexplicable why an attempt to internalize social costs is to be considered a support in the case of renewables - an idea we can only arrive at if we proceed in competition law tacitly from an undiminished right to externalize social costs and demand, in principle, freedom from any social or ecological responsibility. This would reduce to waste paper all the premises of market regulations based on protection of the environment and natural resources.

3. The tilt in the harmonization report: competitive purism for renewable energies - conventional thinking for conventional energies

In order to avoid any misconceptions with regard to the harmonization report and the criticism leveled at it here, let it be said that the report does not say that the directive for the internal electricity market permits no support scheme. In fact, as regards the environmental goals of the EU, it makes explicit provision for "exceptions in the case of agreements limiting competition"***, which are legitimate in the case of renewable energies, and that scrutiny of admissible support must be confined to a check of the proportionality of means. In day-to-day practice, it may be immaterial whether priority arrangements are viewed as an admissible support or as a tariff reflecting more ecological truth in rates and prices. All the same, the distinction between admissible support and non-support is one of principle: psychologically, the concept "support" always suggests what is unusual or temporary, "just within the bounds" of what is allowed and, partly at least, of questionable character, and awaiting repeal. When applied to renewables, however, this attitude is unacceptable in principle wherever, in view of innumerable past and present, direct and indirect subsidies, direct and indirect consequential losses, the market prices of conventional energies fail to reflect either economic or ecological truth. A competition law that abstracts from all this has an apolitical, asocial, anti-economic and anti-ecological character, i.e. it is dangerously dogmatic.

One striking point about the harmonization report of the EU Commission is the fact that the discussion of renewable energies is pegged to a competitive purism that views all forms of obligation to purchase on environmental grounds as being out of step with the market, so that it considers all of them to be limited in time. In this respect, the various provisions of EU law giving priority to renewables on the market - as Gert Apfelstedt worked out in detail - are at most tolerated for the nonce, but not accepted in principle. By contrast, there can be no talk of a comparable purism for markets or competition in the conventional energy sector. Nor does the harmonization report make any mention of the fact that the separation of production, transmission and distribution in accounting and legal respects must be the point of departure for any checks under competition law.

Nor has much attempt been made to thoroughly scrutinize the power supply structures in EU countries that contravene this central principle of the market order, or their pricing criteria and the existing priority rules for conventional electricity with subsidy mechanisms still in place. The fact is that too many blind eyes are still being turned here, the argument being that the "pure teaching" cannot be implemented at once in this case, although it must be applied as a rigorous yardstick in the case of renewable energies. This reveals a double standard that makes it difficult or even impossible to implement wide market penetration by renewables.

This is also true because, in the case of renewable energies, new investment in plant is needed if expansion is to be pursued, whereas conventional power plants are often already written off, which has a cost-cutting effect. That is why priority rules for renewable energies must be put in place for longer periods. A harmonization report only for renewables with none for the entire EU power sector is not acceptable and cannot fail to buttress ongoing discrimination against renewable energies, whereas the market privileges of nuclear or fossil energy sources are only gradually being dismantled - or bypassed.

4. Failure to evaluate successful introduction models

The harmonization report compares practical or theoretical models for the market introduction of renewable energies but at no point makes any attempt to test the practical models for efficacy or successful penetration. This failure is particularly striking because the harmonization report itself, addressing the obligations associated with protection of the global climate, says: "In stepping up the input of renewable energy sources for power generation, the Commission sees an important area for action that can make a crucial contribution toward observing the EU's obligations in this respect." (***) For that reason, it would be expedient to take a closer look at the most successful introduction concepts in the electricity sector available in Denmark, Germany and Spain. Without empirical evaluation, the harmonization report is not a political, but a dogmatic document.

Nevertheless, neither the EU Commission nor the EU Council of Ministers will be able to dispense with a directive for renewables in the electricity sector. The only question is that of the direction to be taken: statutory feed-in, a tendering model as practised in Britain, or a certified quota purchase obligation that is tradable. Also conceivable is an optional system allowing EU member countries to choose between all three models, for a transitional period at least.

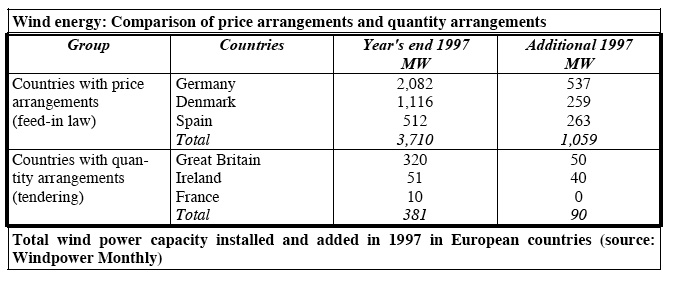

Chart 1

The statutory feed-in arrangements pertaining in Germany, occasionally pronounced dead, have so far withstood all attacks, but even received tailwind from the already cited recommendations of the EU White Paper and the European Parliament - although the new framework of the internal market directive and new national energy sector legislation will certainly call for new criteria to be formulated for the feed-in. This question must be examined, using specifically the available practical experience with actual effects as regards market penetration and conformity with the market economy. Unfortunately, empirical experience has only been available until now on feed-in laws and on the British tendering model. This being so, the following section deals with the British model, the practical operation of which may also point to the necessary criteria and political framework conditions for a quota model.

Limits and contradictions in the British tendering model

The Non-Fossil Fuel Obligation (NFFO) was introduced in Britain in 1989. It obliges regional suppliers to take a certain quantity of electricity from renewable energy sources and to pay defined tariff rates. The original point of this instrument was to support nuclear energy on the privatized British electricity market, so it was not designed for renewables, whose plants are subject to completely different siting requirements in view of the large areas involved.

At irregular intervals, tendering (for precisely defined capacities) is carried out for certain technologies (wind, water, biomass, landfill gas). Photovoltaics is not considered in the NFFO system. For wind energy, two categories were introduced following the negative experience in the first two tendering rounds: smaller-scale projects with a total capacity < 1.6 MW and major projects (wind farms > 1.6 MW).

Between 1990 and mid-1997, there were four tendering rounds. The first (NFFO-1) in 1990 awarded feed-in contracts for 152 MW. The second round followed in 1991 already with 472 MW. The third round was completed in December 1994 and, for the first time, included technologies for biomass gasification. In a departure from NFFO-1 and NFFO-2, sewage gas no longer fell under the tendering system. At year's end 1995, a fourth tendering round was launched, and this was completed in February 1997 with 843 MW. In the tendering procedure, only those projects with the most favourable tenders receive a feed-in contract. The tender price per kilowatt hour is then paid for a limited term (15 years at present). The difference between feed-in tariffs and average pool price, i.e. the price at which conventional electricity is offered on the market, is refunded to the purchasing regional suppliers from funds created by the Fossil Fuel Levy (FFL). This levy is a sort of electricity tax and is paid as a percentage charge by all electricity customers to an especially created authority, the Non-Fossil Purchasing Agency (NFPA).

The tendering procedure is a lengthy, bureaucratic and costly process, both for the operators and for the authorities. However, the main problem is that each tendering round introduces maximum limits, i.e. quotas for the various technologies. As a result, only a fraction of the technical and economic potentials, e.g. in wind energy, is exploited. This impedes natural market developments. Also, the enormous pressure on costs due to competition between tenderers means that only large-scale projects are carried out and in areas with very favourable wind conditions, but often with a sensitive landscape as well. Small private operators or operator communities, as in Germany or Denmark, are practically non-existent, because they cannot keep up financially with the big planning and developing companies, who are often backed by banks and energy suppliers. In Britain, this has led to huge acceptance problems for wind power which go well beyond the occasional local frictions familiar in Germany or Denmark, since the local population in Britain is not included in the project planning. Finally, tenderers often submit unrealistically low tenders owing to the enormous competitive pressures.

One interesting aspect is the implementation rate: in NFFO-2, for example, which is already completed, only about one half of all the wind power projects that had been successful in the tendering were in fact executed. The implementation rate for NFFO-3, in which projects must be completed by 1999, is as low as 15 % for wind energy. Obviously many tenderers are speculating on benefitting from falling plant prices at the last minute. In practice, events seldom turn out that way. If we add up all the wind energy projects implemented so far in the first three tendering rounds in England and Wales, nominal capacity of 200 MW was installed by year's end 1997. If the capacities installed in Scotland and Northern Ireland are included, we have a mere total nominal capacity of 320 MW at year's end 1997. Even if the projects in the third tendering round are implemented before end-1999, the extremely low installation rate in Britain is quite striking.

The crucial argument against this quantity-rated tendering model, however, is the official stipulation of a specific upper limit for renewable energies and the fact that we do not know when it will be extended by political decision. A market whose further unfolding depends on government decisions, while at the same time no defined limits are set to the inputs of nuclear or fossil energy sources, adds up to discrimination against third parties. The tendering procedure means that, institutionally, if the quota were met, further capital spending would have to be suspended for the time being. The consequence would be state constraints on investors going beyond the stipulated quantity (see Table) in the electricity market.

What is more, it can be seen that it is not particularly realistic to expect the government to increase the quota pari passu in order to press ahead with the penetration dynamics. Each redefinition of the quota clashes with conventional power generators' interest in maintaining the status quo, and with their structures. Traditionally, these generators exert great influence in all countries on the formation of the political will, and they complain of losses to the economy if utilization of existing conventional capacities is jeopardized by the operations of new competitors. Basically, their interest is in protecting the status quo, as in a planned economy, in order to avoid stranded investments.

Criteria for a quota model

Even if the British tendering model is not comparable with the model of certified and tradable percentage quotas in the energy market, it can provide some indication of what requirements the quota model must satisfy if it is to be effective in promoting renewable energies.

The quota model entails an ongoing structural conflict between incumbent and auto-/independent producers. While the incumbent generators press for low quotas, on the one hand to protect their own conventional investment and, on the other, to meet the given quota itself - for the purpose of maintaining the generation monopoly - auto-/independent producers will press for high quotas in order to have enough leeway for new investment. So far, they were the pacemakers in renewables. Their further evolution and, hence, pressure on behalf of progressive quotas are crucial to any purposive quota model. This implies that a quota model can only unfold smartly and be capable of extension if separate costing of production, transmission and distribution is in place not only de jure, but most of all de facto as well, and if a state carriage ordinance with a tariff regardless of distance is in force. Distributors actually operating independently and transparently are necessary to ensure that a quota model is not constantly misused as an instrument for underpinning the present producer monopoly and that independent third parties have equal opportunities in serving the quota.

The experience gained with the British model yields further indispensable minimum requirements to be met by a quota model:

- The quota would have to be dimensioned so as to provide wide access for market entry. For example, the short-term goal of a 10 % share for renewable energies by the year 2010 would have to be made a firm and binding target. Also, the quota for gradual rises during subsequent periods would have to be firm from the outset. Implementation of contracts would have to be made binding and non-implementation made subject to sanctions. Whether governments really have the stomach and perseverance to withstand the constant pressures of the established electricity lobby is worth a big question mark.

- It would have to differentiate by region and by renewable energy source in order to avoid one-sided regional concentration and the evolution of a "monoculture" with one renewable energy source.

- If it were introduced as an EU-wide arrangement, it would have to avoid a mere quota trade by imports, with the share of renewables increasing in one country, but with no general rise in the share of renewable energies in the EU. This risk could be avoided by targeting new renewables, i.e. excluding present large-scale water power capacities.

- In addition, it would have to be designed so flexibly that it did not hinder the introduction of some renewable energy source that had made substantial leaps forward in its technology and might already be able to expand beyond its share in the quota. This means: beyond the quota as well, renewable energies need the same rights on the energy market as all conventional energy sources, viz. taking account of environmental merits in their pricing - until there is an EU energy tax on conventional electricity.

Thus, a quota model, too, requires an unlimited, non-discriminatory statutory feed-in guarantee for all initiatives on behalf of renewables beyond the current quota. However, the criteria named here for renewable energies do not apply in the same way to the marketing of electricity from block-type thermal power stations based on fossil energy sources, for which a quota model is proposed in this edition of the periodical. The present state of the art in block-type thermal power plant station technology can be universally deployed, and there is no risk of one-sided regional concentrations. Since no certified tradable quota model exists in practice, it should undergo its practical testing first of all in the block-type thermal power station sector. The significance of statutory feed-in rules covering the entire electricity market is that they offer considerable market certainty without bureaucratic outlays, which is indispensable for the introduction phase of renewable energies, and the possibility of penetrating the market without a quota. Also, they have a much stronger impact on the desired structural change in energy use types, because the existence of, and undiscriminated free market access for, auto-/independent operators means that incumbent producers, too, tend to go over to investing in renewables. The result is priority for statutory feed-in rules and a corresponding EU directive, albeit according to the criterion of the EU directive, which the EU White Paper, too, follows in its thinking.

Tradable certified quotas to complement feed-in tariffs are an option, therefore; as a minimum quantity that distributor firms must offer in order to encourage investment if there is no feed-in in line with the quota. So the justification for a complementary quota model to define certain purchase quantities for a distributor firm follows from the goal of having the widest possible regional market penetration for all renewable energies. In fact, the electricity feed-in law in Germany has come to bear so far only in the case of wind power and water power and - in Denmark- biomass as well. However, the idea behind market penetration is that all renewable energies benefit, and in all regions. This can be implemented only by having direct regional surcharges with a breakdown by renewable energy source in the feed-in laws, which is a very cumbersome procedure, or by having purchase obligations for distributor companies, which they could possibly only meet by taking advantage of permitted surcharges.

The criteria of a statutory feed-in and the options

The obvious and most promising approach for a European feed-in directive is that of adding a direct and indirect calculation of the external costs of conventional electricity supplies to the electricity price by an appropriate surcharge.

The basic criterion in this connection should be the avoided purchasing costs of the firm offering the electricity, if that firm, instead of conventional electricity, has to supply electricity from renewable energy sources. All that can be said against this basic criterion, in fact, is the lump-sum nature of the feed-in tariffs if this fails to distinguish between different daily load times. Hence, a basic tariff for different daily time zones might be provided for in a later step, so that the electricity fed in during peak load times is remunerated by analogy with the avoided purchasing costs for peak load electricity, and if much the same is done for centre and base load times.

The second criterion building up on the basic criterion must be the environment premium (priority option A), with merely the specific amount being left open to discussion. Indications of the amount follows from a rough calculation of the external costs of conventional power generation that are avoided by renewable energies and, for that reason, justify the surcharge. This second criterion might be replaced by an equivalent criterion only when an ecologically based energy tax on conventional energies has been introduced at national or EU level from which renewables are excepted. The precondition is that this energy tax is high enough - meaning actual payment of external costs (priority option B).

The difference between these two options is that option A - i.e. without energy tax on conventional electricity - will hold the electricity price level lower in the long run than option B, because it is cheaper for the electricity supplier merely to pay the cost of the environment premium than to compensate the external costs of the entire amount of conventional electricity by way of energy taxes. Option B should be preferred, therefore, because - with the same impetus for the market introduction of renewable energies - it also contributes toward enhancing overall energy efficiency.

At all events, both options would have to be regarded as minimum EU-wide standards which member states are allowed to exceed. Also, they do not render superfluous a separate support programme for photovoltaics - e.g. in the form of the 1 million plant programme likewise recommended by the EU Commission.

In the case of option B, European feed-in arrangements for renewable energies would have to be introduced at the same time as an EU electricity tax for conventional energies. Option A is to be preferred until a decision on such a tax is taken and might later be replaced by option B. In option A, the extra cost of the environment premiums would have to be borne by all electricity suppliers in order to avoid distortions from different feed-in focuses. In option B, this would no longer be necessary.

Within the scope of the priority options, however, differentiation, too, seems to be appropriate in the case of wind power plants in order to avoid serious regional concentration. Higher priority tariffs in low wind areas, however, constitute a subsidy element, to finance which a national transfer procedure would be the suitable instrument. It can be justified by a desire to have a balance in the landscape used for wind power plants. If this subsidy variant is to be avoided, it would be necessary to come back on the complementary purchasing quota of the regional distributor firm as discussed in the previous section.

1 COM (97) 599 final version on 26 November 1997, "Energy for the Future: Renewable Energy Sources - White Paper for a Community Strategy and a Plan of Action"

2 EUROSOLAR Memorandum on the EU Commission's Green Paper "Energy for the Future", in: Solarzeitalter, no. 1/1997, pp. 3 ff.

3 EUROSOLAR: EURERULE. Legal, technical, administrative and structural conditions for Common Feed-in Rules in the EU for electricity generated with renewable energy sources (RES) by auto-producers. Final Report.

4 Directive 96/92/EC, 19 December 1996

5 COM (97) 599 final version, op cit. (FN 1)

6 AA-0207/98 - Resolution on the memorandum of the Commission COM (97) 0599-(4-0047/98)

7 COM (98) 167 final version dated 24 March 1998, Report of the Commission of the Council and the European Parliament on harmonization requirements: Directive 96/92 EC regarding common provisions for the internal electricity market.

8 Gert Apfelstedt: Vorrangregelung für Ökostrom unterm Damoklesschwert?, ZNER 1/1997, pp. 3 ff.